Background

Classic seminal paper on RPC with goal to make remote communication accessible to as many programmers as possible.

Note:

- Exporter - server that implements the interface

- Importer - client that calls the interface

Goals

- Remote procedure calls - useful paradigm for providing communication across a network between programs written in a high-level language

- Present a package that provides an RPC implementation

- RPC mechanism

- Binding of RPC clients

- Transport level communication protocol

Introduction

Prior RPCs knowledge:

- Procedure calls - Transfer of control and data of a program running on a single computer

- Now RPC is procedure calls over a network.

- When an RPC is invoked:

- The calling environment is suspended

- Parameters are passed across the network to the environment where the procedure is to execute

- The desire procedure is executed there

- When the procedure finishes and produces its results, the results are passed back to the calling environment

- The calling environment resumes Why RPCs:

- Clean and simple semantics - easier to build distributed computations

- Efficiency - procedure calls seem simple enough

- Generality - in single-machine computations, procedures are often the most important mechanism for communication between parts of the algorithm Their RPC package:

- Built for use within Cedar programming environment for Xerox

- for single-user workstations

- Computers - Dorados - 24bit addr and 80 megabyte disk

- Comms - 3 megabit / sec ethernet

- Mesa programming language 💀

Goals

- Primary - make distributed computation easy

- make it as easy as local procedure calls

- semantics of RPCs should be as close to procedure calls as possible

- Secondary:

- RPC highly efficient

- Secure communication with RPC

Design Decisions

- Didn’t remote fork

- Didn’t emulate shared address space

- network layer didn’t support that at the time

- semantics of RPCs should be as close to procedure calls as possible

- Chose to have no time-out mechanism (prevent complexity lol)

Structure

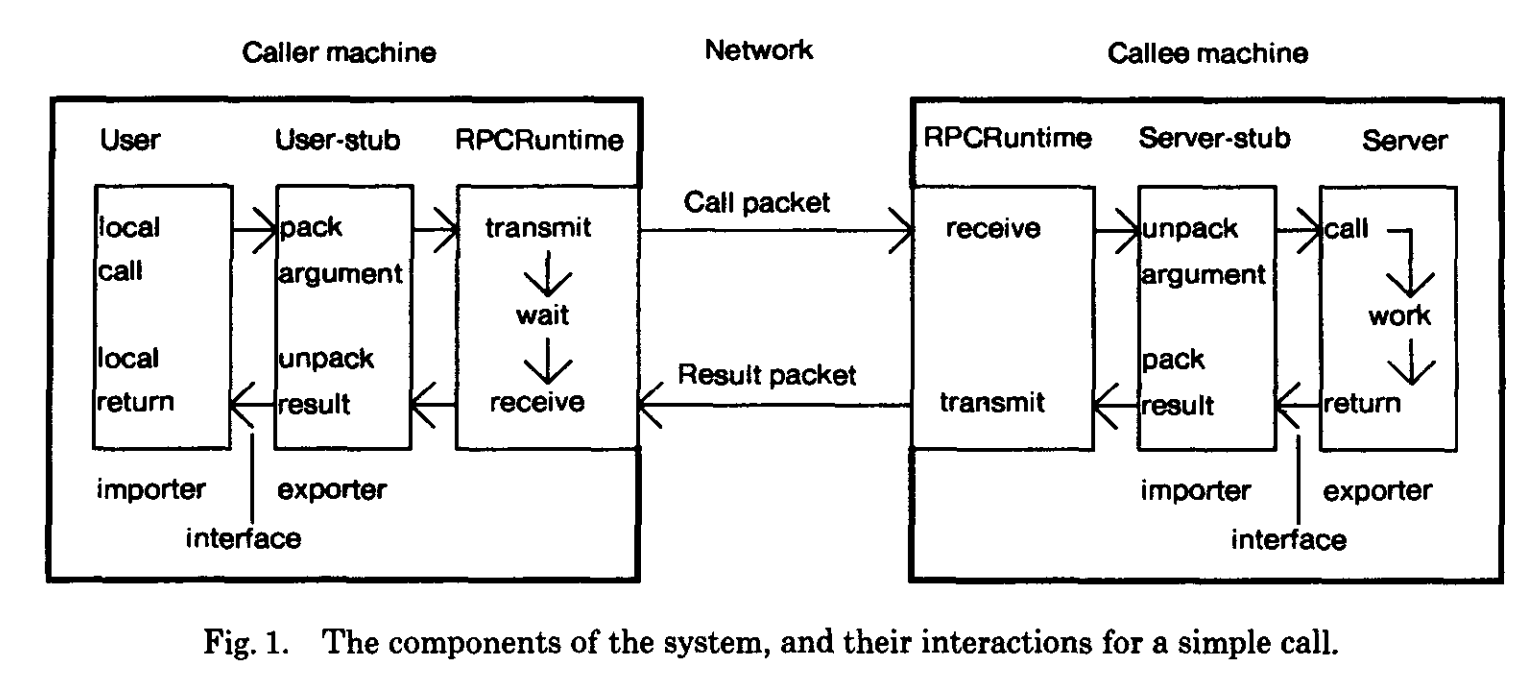

Uses stubs and specifically 5 pieces of the program are involved:

-

user - caller

-

user-stub - placing specification of the target procedure and arguments into packets

-

RPC communications package (RPC runtime) - trasmit these reliably to the callee machine

-

server-stub - unpacks packets and makes a local call

-

server - callee Once server completes returns to the user in reverse

-

RPCRuntime is a standard part of the Cedar system.

-

The user-stub and server-stub are automatically generated by a program called Lupine

- Parallels to

protocand protobuf stubs - Programmer only has to design the interface, Lupine is responsible for generating the code for packing and unpacking arguments and results

- RPCRuntime is responsible for packet-level communications

- Parallels to

Binding

Two aspects to consider:

- How does client of the binding mechanism specify what he wants to be bound to?

- Question of naming

- How does a caller determine the machine address of the callee and specify to the callee the procedure to be invoked

- Question of location

Naming

- “Bind” interfaces together from caller to callee

- Interface has two parts:

- type - specify which interface the caller expects the callee to implement

- instance - specify which particular implementor of an abstract interface is desired

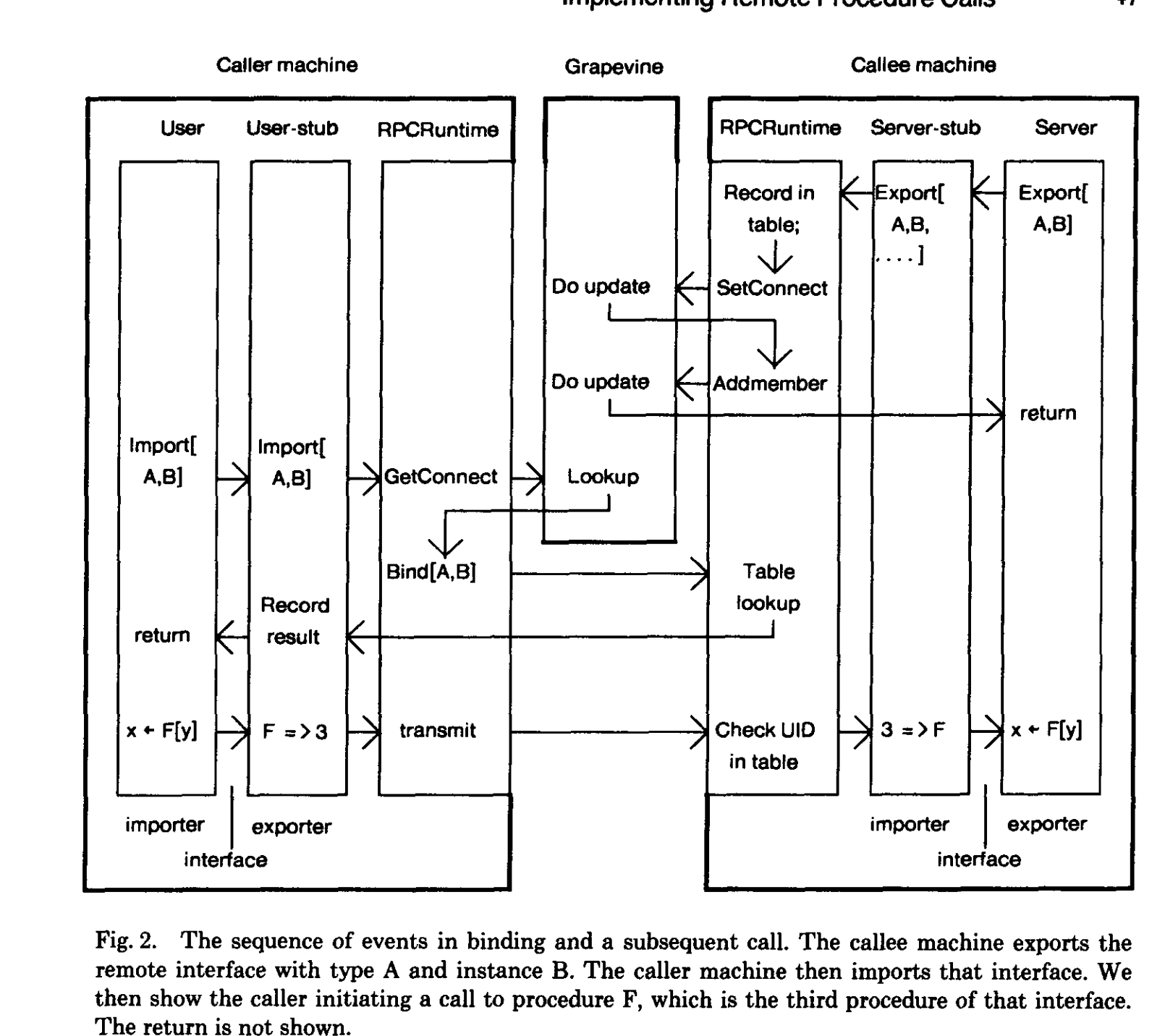

Locating an Appropriate Exporter

- Uses Grapevine distributed database for RPC binding (old ah mail db)

- highly reliable and data is replicated → look up missing is low

- Grapevine’s db consists of set of entries, keyed by string (Grapevine RName), and has two varieties of entries: individuals and groups

- For every individual there is:

- A connect-site or the network address

- For each group there is:

- A member-list - list of RNames

- RPC Package maintains two entries in the Grapevine data based for each interface name

- One for each type

- One for each instance

- Both type and instance are Grapevine RNames

- For every individual there is:

Server exports interface:

- Update Grapevine individual for instance

- Check if instance is of type’s group

- Server stores local binding metadata:

- interface type and instance

- dispatcher fn pointer

- unique 32-bit id

Client imports interface:

- Ask Grapevine for instance’s connect-site

- Contact machine and ask for binding info

- Client stub stores the binding

- Server network addr

- dispatcher table index

- unique export id

Note: They use a unique identifier scheme which means that the bindings are implicitly broken if the exporter crashes and restarts (since the currency of the identifier is checked on each call)

- correct semantics because user won’t be notified of a crash happening between calls

- allows calls to be made only on procedures that have been explicitly exported through the RPC mechanism

Packet-Level Transport Protocol

Requirements

- Minimize elapsed real-time between initiating a call and getting results

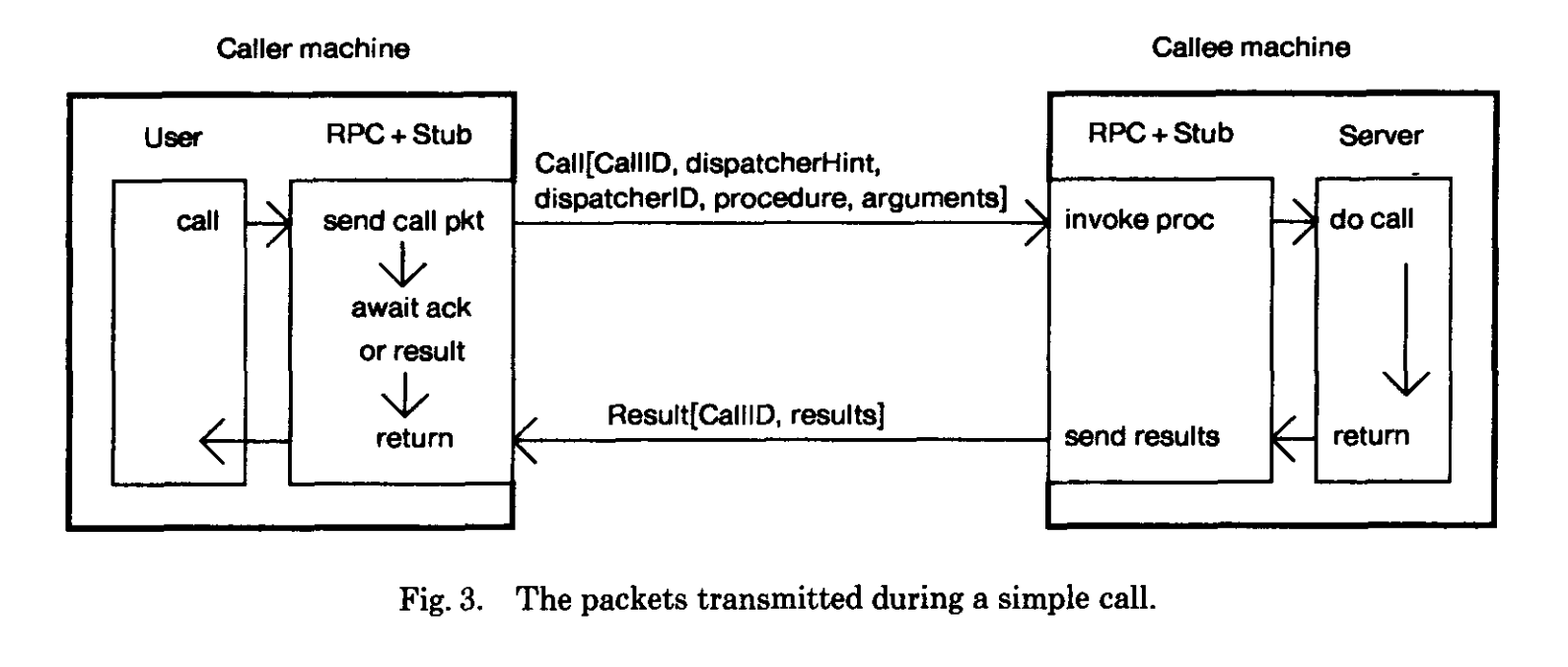

Simple Calls

To make a call:

- Caller sends a call packet contains:

- a call id

- data specifying the desired procedure

- args

- Callee machine receives this packet and appropriate procedure is invoked

- When procedure returns, the callee sends back a result packet containing:

- call id

- results

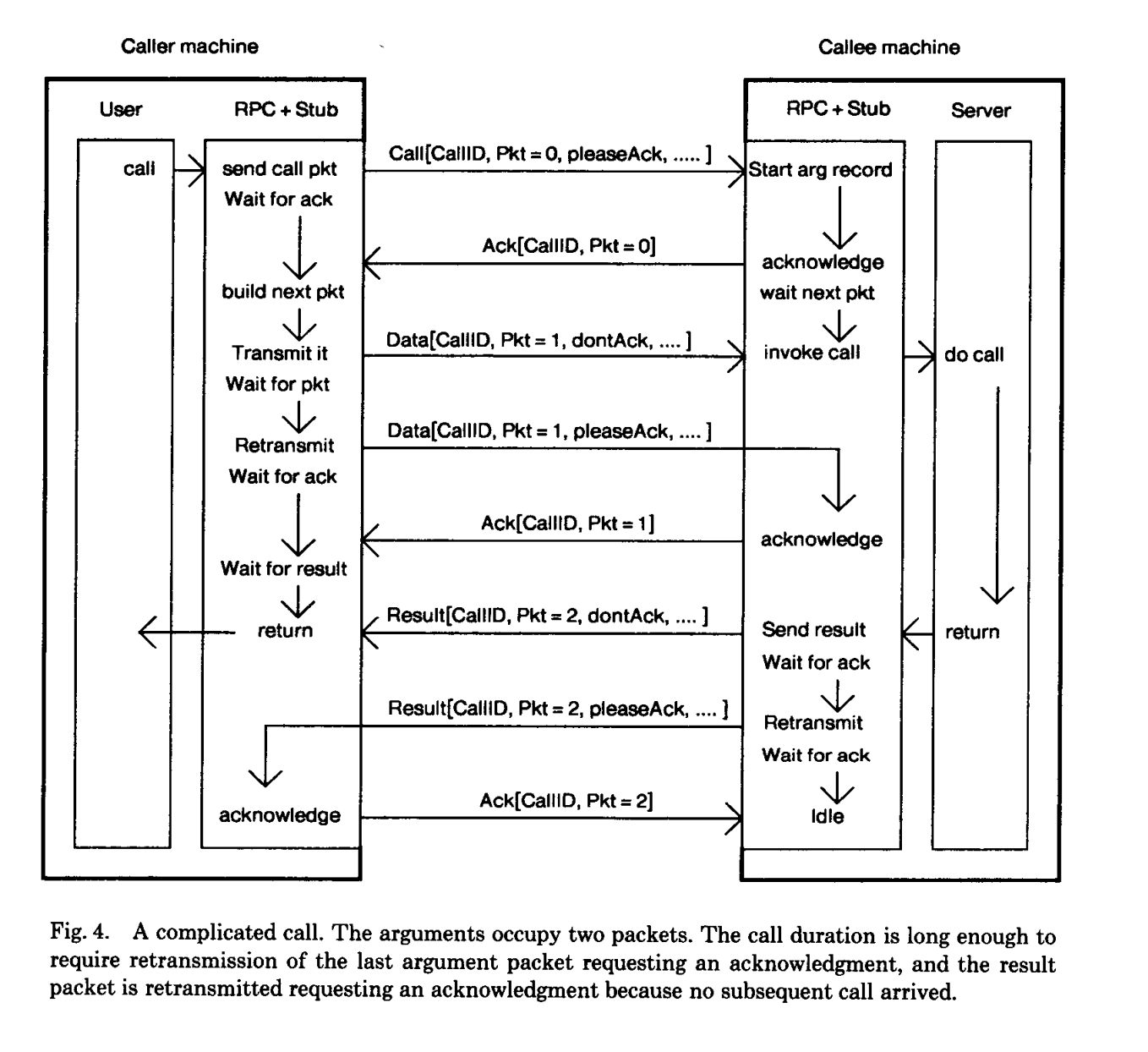

Complicated calls

The transmitter of a packet is responsible for retransmitting it until it’s acknowledged

- While waiting, the caller periodically sends a probe packet to the callee which the callee is supposed to acknowledge. Health check with graduate increase between iterations If arguments or results are too large to fit in a single packet, they are sent in multiple packets with each but the last requesting explicit acknowledgment