Preface

The goal here is to summarize information presented in the book The Missing Readme by Chris Riccomini and Dmitriy Ryaboy in the lens of a new grad. There are two interesting avenues that I want to gain from this:

- To take a snapshot of what an early career thought process looks like and compare when I become more mature as an engineer

- To compartmentalize important soft skills prior to working

Framework: systems/info that can be integrated into thought process/workflow Action Item: an action that can be taken

Chapter 1: The Journey Ahead

Your Destination

You need to be competent in several core areas (requirements):

- Technical Knowledge

- Execution - you create value by solving problems with code and understand the connection between your work and the business

- Communication:

- clearly in both written and verbal form

- give and receive feedback effectively

- proactively ask for help and get clarification in ambiguous situations

- note: adding also how to identify ambiguity

- raise issues and identify problems in constructive manner

- provide help when possible, starting to influence peers

- document your work

- write clear design documents and invite feedback

- patient and empathetic when dealing with others

- leadership:

- Work independently on well-scoped work

- learn from mistakes quickly

- handle change and ambiguity well

- actively participate in project and quarterly planning

- help new team members onboard

- give meaningful feedback back to your manager

Roadmap

Framework: Peak Newb → Ramp-Up River → Cape Contributor → Operations Ocean → Competence Cove

Peak Newb

Building familiarity:

- With team, company

- How things are done

- Onboarding, etc

ACTION ITEM: Contribute by filling documentation gaps you find in the onboarding process

ACTION ITEM: Typically companies might have a new hire orientation, if not ask manager to explain the “org chart” to get a sense of the org structure.

Ramp-Up River

Once you’ve completed newbie tasks, you take on first real work.

ACTION ITEM: Ask questions and have team review your work frequently. Investigate how the code is built, tested and deployed. Read PRs and code reviews.

ACTION ITEM: Build a relationship with your manager

- get to know their working style

- understand their expectations

- talk to them about your goals

- ASK how to communicate status, managers usually want to track progress

Cape Contributor

Identified by working on larger tasks/features. You should be actively helping teammates and be involved in code reviews.

ACTION ITEM: Participate in team planning and work with manger to set goals or objectives and key results (OKRs)

Operations Ocean

Understanding how code behaves in users’ hands. On call experience and learning how to protect your software.

Competence Cove

You’re able to drive a small project now. You’ll need to write a technical design document and help with project planning.

Now here is the time to work on longer-term goal setting and performance reviews. Prior should be getting to the point to be a competent team member.

Chapter 2: Getting to Conscious Competence

Martin M. Broadwell defines four stages of competence:

- unconscious incompetence - unable to perform a task correctly and are unaware of the gap

- conscious incompetence - unable to perform a task correctly but are aware of the gap.

- conscious competence - capable of performing a task with effort

- unconscious competence - capable of performing a task effortlessly

Framework: Front-Load Your Learning

- spend first few months on the job learning how everything works

- helps with the needed context to participate in design discussions, on-call rotations, operational issues, and code reviews

Framework: Allocate time for reading

- team documentation

- design documents

- code

- tickets

- backlog

- books

- papers

- technical sites

Action Item: Go to brown bags (informal lunch talks) and tech talks if company offers them to gain relevant information

Shadowing - following another person as they perform a task, setup time before the shadowing session for planning and retrospection. Take notes and ask questions

Pair programming - two engineers write code together

Asking Questions

Framework:

- Do your research: internet, documentation, READMEs, source code, bug trackers, unit test, internal communications

- Timebox your research: prevent churn

- Show your work: frame your question using your research

- Don’t interrupt: identify whether the team member is busy, make sure to understand company convention

- Perfer multicast, async communication

- Post questions where multiple people can respond at their own pace

- Batch Your Synchronous Requests - setup a dedicated time with your tech lead or manager for nonurgent questions. Write down questions and hold them until the meeting. BE PREPARED

Overcoming Growth Obstacles

Imposter Syndrome - recognize growth and label positive feedback Dunning-Kruger - Be open to being wrong, cultivate a mindset of trade-offs, not of right and wrong

Chapter 3: Working With Code

Software Entropy

The drift towards disarray with changes

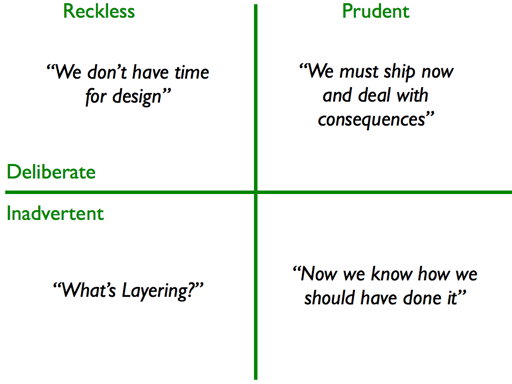

Technical Debt

Technical decisions that you disgree with are not technical debt. Neither is code that you don’t like. To be debt, the problem must requre the team to “pay interest”, or code must risk triggering a critical problem.

Image from https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TechnicalDebtQuadrant.html

Image from https://martinfowler.com/bliki/TechnicalDebtQuadrant.html

Important takeaway: Some debt is unavoidable, as you can’t prevent inadvertent mistakes. But growing from it and recognizing tradeoffs is important to keep in mind when accessing for technical debt

Addressing Technical Debt

Framework:

- State the situation factually

- Describe the risk and cost of the debt

- Propose a solution

- Discuss alternatives (including not taking action)

- Weigh the trade-offs

- Make your proposal in writing (note: quote)

Changing Code

Framework:

- Identify change points

- Locate the code that needs to be changed

- Find test points

- Find entry points into the code that you want to modify, areas that tests invoke and inject into

- Break dependencies

- changing the code structure so it’s easier to test, must not change behavior

- Write tests

- verify old behavior

- Make changes and refactor

Framework: ideals to follow when changing code:

- leave code cleaner than you found it

- make incremental changes, separate PRs, get buy-in from your team before refactoring spree

- be pragmatic about refactoring

Framework: Avoiding pitfalls when changing code:

- use boring technology, use what is battle tested

- don’t ignore your company’s or industry’s standards just because you don’t like them

- don’t fork without committing upstream

- resist the temptation to rewrite

Chapter 4: Writing Operable Code

Defensive Programming

Framework: Make code safe and resilient:

- immutable variables

- access modifiers to restrict scope

- static type checkers

- validate inputs

- use exceptions and make precise ones

- retry with backoff

- write idempotent systems

- clean up resources

Logging

- Framework: Use log levels:

- TRACE - fine level of detail, line by line

- DEBUG - useful for production issue but not during normal operations

- INFO - nice to have info about state of application, not issues, but only useful information during normal operations. “just in case” logging goes into TRACE or DEBUG

- WARN - potentially problematic situations

- ERROR - “last gasp” log messages

- Keep logs atomic: all relevant info in one line

- Keep logs fast

- Don’t log sensitive data

Metrics

- Types of metrics:

- Counters - measures number of times an event happens

- Gauges - are point-in-time measurements that can go up or down

- Histograms - breaks events into ranges based on their magnitude

- Framework: measure everything, measurements are cheap

- resource pools - gauge the size of resource pook

- caches - count cache hits and misses

- data structures - measure size of key data structures with gauges

- CPU-intensive operations - time CPU-intensive operations

- I/O-intensive operations - measure the size of data your code deals with, track the size of data generated for I/O using histograms, goal is to see percentile data sizes

- Data size - ^

- Exceptions and errors - count every exception, error response code, and bad input

- Remote requests and responses - measure any requests to your applications, outliers can tell a story that something is wrong

Traces

Distributed call trace - stitches together downstream RPC calls

Configuration

Framework: avoid dynamic configuration when possible, don’t get too creative, use standards

- log and validate all configuration

- provide defaults

- group related configuration:

- eg

timeout: { duration: 10 , units = seconds }

- eg

Framework: Don’t blindly copy things without actually understanding what they do or how they work

Chapter 5 - Managing Dependencies

Good Versioning Practices

- Unique - versions should never be reused

- Comparable - versions should help humans and tools reason about version precedence

- Informative - versions differentiate between prereleased and released code

Semantic Versioning

For the SemVer semantic: Version numbers are combined into a single <MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH> number

- eg:

httpclientversion 4.3.6 - patch versions are incremented for backward-compatible bug fixes

- minor versions are incremented for backward-compatible features

- major versions are incremented for backward-incompatible changes

Transitive Dependencies

Dependencies may depend on other libraries, those libraries are then called transitive dependencies

Typically organized into a dependency tree

Dependency Hell

Conflicting versions of the same library or incompatible library upgrade can break builds and cause runtime failures.

- Circular dependencies

- Diamond dependencies

- Version conflicts

Avoiding Dependency Hell

- Do you really need the dependency?

- How well maintained is the dependency?

- How easy would it be for you to fix the dependency if something went wrong?

- How mature is the dependency?

- How frequently does the dependency introduce backward-incompatible changes?

- How well do you, your team, your organization understand the dependency?

- How easy is it to write the code yourself?

- How is the code licensed?

- What is the ratio of code you use versus code you don’t use in the dependency?

Isolate Dependencies

Be pragmatic; don’t be afraid to copy code if it helps you avoid a big or unstable dependency

Dependency Shading - reloading a dependency into a different namespace to avoid conflicts; use sparing as it can confuse developers with different naming

Chapter 6 - Testing

Types of tests

- Unit tests

- Integration tests

- System tests - verify a whole system, e2e

- Synthetic monitoring scripts run in prod to simulate user registration, browse for and purchase an item

- eg: Playwright

- Performance tests - load and stress tests, measure a system performance under different configurations

- answers the questions from SLOs

- Acceptance tests - performed by a customer, or their proxy, to validate that the delivered software meets acceptance criteria

Mocks

Framework: watch out for mocks with complex internal logic or shared state between tests. The more complex it is, the more brittle the test. Reliance on mocks is a code smell that suggests tight code coupling.

Code Quality Tools

- Static code analyzers - checks source code for common mistakes, looks for code smells

- Code style checkers - checks source code formating

- Code complexity tools - checks for overly complex logic by calculating cycolmatic complexity or paths in code

- Code coverage tools - measures how many lines of code were exercised by the test suite

- Framework: rule of thumb - 65 - 85% coverage

Determinism in Tests

- nondeterministic tests degrade test value, flaky/flapping

- seed RNGs

- don’t call RPCs in unit tests

- inject clocks

- called dependency injection - allows tests to override clock behavior by injecting a mock into the clock parameter

- avoid sleeps and timeouts in multithreaded test, try to make it deterministic instead

- slows down or stalls testing

- Bind to port zero

- forces OS to pick an open port, static port allocations can cause nondeterminism

- Generate unique file and database paths

- isolate and clean up left over state

- don’t depend on test order

- use setup and teardown to share logic between tests

Chapter 7 - Code Reviews

Reviews can also serve as documentation explaining why code is written in a certain way

Code Review Considerations

- Frame review - provides context and reviewers

- De-risk with draft reviews - draft pull request to get some feedback on code direction

- Walk through large code changes - prepare relevant design docs and code in advance

- Don’t get attached to code - be able to distill the critiques of the code

- Be proactive

How to Review Code?

- Triage Review Requests: focus on urgency, changes that you cna learn from and those who touch code that you are familiar with

- Block Off Time for Reviews

- Understand the Change

- Give Comprehensive Feedback

- Acknowledge the Good Stuff

- Distinguish between Issues, Suggestions, and Nitpicks

- add levels of importance to feedback

- eg:

Nit: Double space. Nit: Here and throughout, use snake_case for methids and PascalCase for classes. Nit: Method name is weird to me. What about maybeRetry(int threshold)

- Don’t Rubber-Stamp Reviews (hasty approvals)

- Don’t limit yourself to Web-Based Review tools

- Don’t Forget to Review Tests

- Drive to a Conclusion: add a review summary if a lot of comments

Chapter 8 - Delivering Software

You should understand how your code winds up in front of users.

Software Delivery Phases

- Build - software built into packages (immutable and versioned)

- Release - packages then are released (release notes, changelogs are updated and published into a centralized repository)

- Deployment - deployed to preproduction and production environments (not yet accessible to users just installed)

- Rollout - shifting users to new software

Branching Strategies

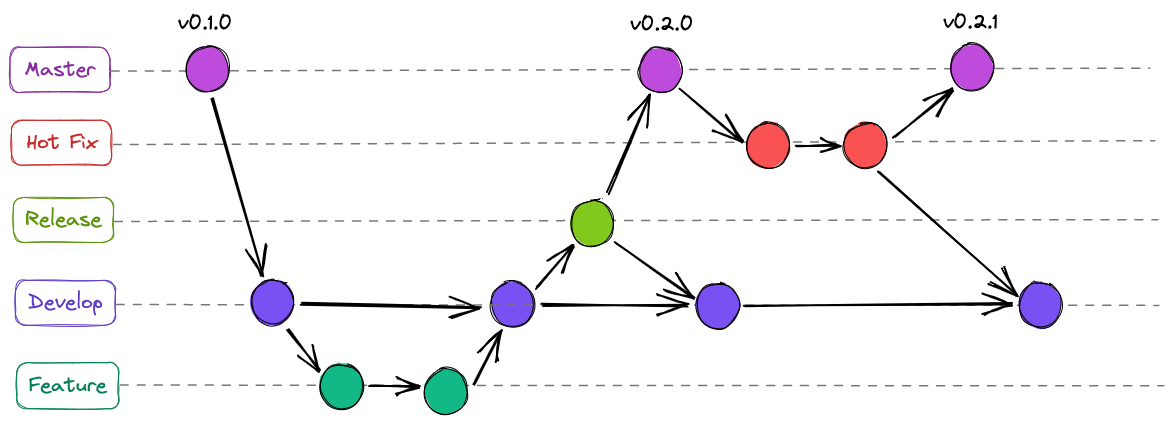

Trunk-based development - all developers work off a trunk (main), branches are used for single small feature, bug fix, or update

- works best when branches are merged back to trunk quickly (mitigating divergence)

- finds bugs and incompatibilities early

- Issues:

- bugs in trunk will slow down all developers

- reliance on fast automated tests Feature branch-based development - many developers simultaneously work on long-lived feature branches

- developers need to rebase often to prevent divergence

- when a release is being prepared, feature branches are pulled into the release branch, packages are built off stable release branches

- common for when trunk-based is too unstable to release to users and developers want to avoid entering a feature freeze (commits are banned while trunk stablizes)

Gitflow - popular feature branch approach

- Uses a development branch, hotfix branch and release branch

- development: used as main that feature branches merge and rebase with

- release: cut from development branch when a release is prepared

- hotfix: critical bug that are addressed immediately that are applied to hotfix branch and merged into both trunk and develop branch

Note: master here is trunk

Note: master here is trunk

Build Phase

Packages - prebuilt software for a platform or environment

Framework: Package Considerations:

- Version Packages

- Package Different Resources Separately

Release Phase

Art of publishing stable, well-documented software at a predictable cadence

Framework: Release Considerations

- Don’t throw releases over the fence - take responsibility for your software’s release, make sure your code works in test environments, keep track of release schedules

- Publish packages to a release repository

- Keep releases immutable - once published, never change or overwrite a release package

- Release frequently

- Be transparent about release schedules

- Publish changelogs and release notes

Deployment Phase

Framework: Deployment Considerations

- Automate deployments

- Make deployments atomic

- Deploy applications independently

Rollout Phase

Framework: Rollout Strategies

- Feature flags

- control percentage of users receive one code path vs the other

- sometimes used in A/B testing - a technique for measuring user behavior with a new feature

- circuit breakers - automatically switch code paths when there’s trouble

- dark launches

- releasing new features in production but hiding them from users (e.g., behind a feature flag or toggle)

- an example implementation is using a loadbalancer to route to both live service and dark service, making sure to avoid deduplication errors and side effects

- Diffy, open source tool, sends dark traffic to three instances of the backend service: two running prod and one with release candidate. Diffy then compares responses and identify differences, helping to insure consistency.

- Use case:

- Test performance, infrastructure impact, or integration without exposing to end-users.

- Collect usage data silently.

- canary deployments

- gradually rolling out a new version of software to a small subset of users or servers before wider release.

- an example implementation is using a loadbalancer to route a percentage of inbound traffic to canary release

- Use case:

- Minimize blast radius of bugs.

- Monitor metrics (e.g., errors, latency) before full rollout.

- blue-green deployments

- Maintain two identical environments:

- “Blue” (currently live)

- “Green” (new version).

Once green is tested and ready, traffic switches from blue to green.

- an example implementation is using a loadbalancer to route 100% inbound traffic to green release, but keep blue passive to be able to switch back

- Use case:

- Instant rollback: just switch back to blue if green fails.

- Zero downtime deployments.

- Maintain two identical environments:

Monitor Rollouts Determine what the general health metrics are or service level indicators(SLIs)

Chapter 9 - Going On-Call

First line of defense for any unplanned work (production issues or ad hoc support requests)

How On-Call Works

On-call devs rotate based on a schedule, often a week or two

- some schedules have primary and secondary on-call developers

- some organizations have tiered response structure

Most of an on-call’s time is spend fielding ad hoc support requests such as bug reports, questions about how their team’s software behaves, and usage questions. On-calls triage these requests and respond to the most urgent

Paging - on-call devs get paged for critical alerts

handoff - all on-call rotations should begin and end with a handoff. the previous on-call developer summarizes any current operational incidents and provides context for any open tasks to the next on-call developer.

Important On-Call Skills

- Make yourself available - “your best ability is availability”

- “A fast response is generally expected from the on-call engineer, but not necessarily a fast resolution”

- Be on the lookout for incidents

- pay attention to a multitude of communication channels

- proactively read release notes and any channels that list operational information

- create a list of resources that you can rely on in an emergency:

- links to critical dashboards and runbooks for your services

- instructions for accessing logs

- important chat rooms

- troubleshooting guides

- Prioritize work so the most critical items get done first

- Framework: Clear communication

- Concise sentences

- Respond quickly:

- Show that you’ve seen request + understand problem

- Example: “Thanks for reaching out. To clarify: the login service is getting 503 response codes from the profile service? You’re not talking about auth, right? They’re two separate services, but confusing named”

- Post status updates periodically:

- Include what you’ve found since last update + next task + time estimate

- “I looked at the login service. I don’t see a spike in error rate, but I’ll take a look at the logs and get back to you. Expect an update in an hour.”

- Write down what you’re doing as you go

- include timestamps in notes to help operators correlate events across the system when debugging issues

Steps to Handle an Incident On-Call

Top objective: mitigate the impact of the problem and restore service Second objective: capture information to later analyze how and why the problem happened Third objective: determining the cause of the incident, proving it to be the culprit and fixing the underlying problem

Incident Response Steps

- Triage: Engineers must find the problem, decide its severity, and determine who can fix it

- Coordination: Teams (and potentially customers) must be notified of the issue. If the on-call can’t fix the problem themselves, they must alert those who can

- Mitigation: Engineers must get things stable as quickly as possible. Mitigation is not a long-term fix; you are just trying to “stop the bleeding”. Problems can be mitigated by rolling back a release, failing over to another environment, turning off misbehaving features, or adding hardware resources.

- Resolution: After the problem is mitigated, engineers have some time to breathe, think, and work toward a resolution. Engineers continue to investigate the problem to determine and address underlying issue. The incident is resolved once the immediate problem has been fixed.

- Follow-up: An investigation is conducted into the root cause—why it happened in the first place. If the incident was severe, a formal postmortem, or retrospective, is conducted. Follow-up tasks are created to prevent the root cause (or causes) from happening again. Teams look for gaps in the process, tooling, or documentation. The incident is not considered done until all follow-up tasks have been completed.

Providing Support

When on-call engineers aren’t dealing with incidents, they spend time handling support requests

Chapter 10 - Technical Design Process

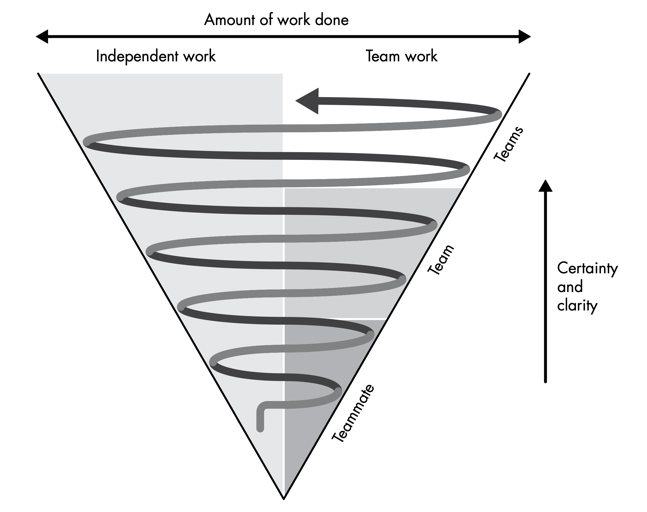

Technical Design Process Cone

How designs are made

How designs are made

Thinking About Design

Framework:

- Define and understand the problem (or problems) that you’re trying to solve

- Understand the boundaries of the problem to avoid building the wrong thing

- Start by asking stakeholders

- “What happens if we don’t solve this problem?”

- Do your research

- Engineering blogs

- industry conferences

- talk to experts

- think critically

- Conduct experiments

- draft APIs and partial implementations

- run performance tests or even A/B user tests

- circulate prototypes with your team to get feedback, focus on illustrating or testing your idea don’t write tests or polishing code

- Give it time

Writing Design Docs

- How to decide when a design doc is needed:

- Framework:

- Requires more than 1 month of engineering work

- The change will have long-lasting implications with regard to extending and maintaining the software

- The change will significantly impact other teams

- Framework:

- Why you should write:

- Writing has a way of exposing what you don’t know

- Push to explore the problem space and solidify understanding

- Easier to solicit feedback on a written design

- Spreading design knowledge will help others maintain an accurate mental model of how the system works

- Helpful for engineers that are new to the team

- Writing has a way of exposing what you don’t know

- Learn to write:

- Writing is a lossy method of information transfer

- you’re taking your ideas and writing them down, and your teammates are reconstituting your ideas imperfectly in their minds

- Good writing improves the fidelity of this transfer

- Writing is a lossy method of information transfer

- Keep design docs up-to-date:

- Living Documents - design docs that morph from proposals into documents that describe how software is implemented

- Two pitfalls during the transition from proposal to documentation

- implementations diverge - the document is misleading to future users

- prior context/history is loss with new updates - future developers can’t see discussions that led to design decisions and might repeat mistakes of the past

- Two pitfalls during the transition from proposal to documentation

- version control your design documents

- Living Documents - design docs that morph from proposals into documents that describe how software is implemented

Using a design doc template

- Framework: Template examples:

- Python Enhancement Proposals

- Kafka Improvement Proposals

- Rust Request for Comments (RFCs)

- Framework: Generic Template

- Introduction

- Introduce the problem and why it’s worth solving

- Paragraph-long summary of the proposed change and guidence that points to different readers — security engineers, operations engineers, data scientists — to relevant sections

- Current State and Context

- Describe the architecture that is being modified and define terminology

- Explain what systems with nonobvious names do!

- Are there workarounds being employed? What are their drawbacks?

- Motivation for Change

- Why is this particular problem worth solving and why now?

- Describe the benefits that will result from this effort and tie to business needs

- Requirements

- List requirements that an acceptable solution must meet:

- User-facing requirements: define the nature of the change from a user perspective

- Technical requirements: hard requirements on the solution that must be met, usually caused by interoperability concerns or strict internal guidelines

- Security and compliance requirements: addresses security needs, data retention and access policies are often covered here

- Other: critical deadlines, budgets and other important considerations

- List requirements that an acceptable solution must meet:

- Potential Solutions

- Proposed Solution

- Design and Architecture

- highlight implementation details of interest, such as key libraries and frameworks being leverage, implementation patterns, and any departures from common company practices

- Includes: block diagrams of components, call and dataflow, UI, code, API, and schema mock-ups

- System Diagram

- Diagram that shows the main components and how they interact

- Highlight changes with before and after and notes on the changes

- UI/UX Changes

- create mock-ups to walk through a user’s activity flow

- or dev ex with library you’re creating

- Code Changes

- Describe implementation plan and any new abstractions

- API Changes

- error handling should also be included here

- Persistence Layer Changes

- explain storage technologies being introduced or modified

- include all schema changes

- Test Plan

- explain how you plan on verifying your changes

- Rollout Plan

- document the feature flags you will need to put in place to control the rollout

- Unresolved Questions

- Explicitly list pressing questions that have not yet been answered in the design

- Appendix

- Extra details of interest: related works and further readings

- Introduction

Collaborating on Design

- Understand your team’s design review process

- notify architects of large upcoming changes and gives leads a chance to provide feedback

- common patterns: Architectural review boards and “request for decision” processes

- Architectural reviews - formal, heavier-weight process that requires approval from outside stakeholders such as operations and security

- don’t wait on final approval before writing code

- implement prototypes and proof-of-concept “spikes” to increase confidence in the design

- request for decision or RFD

- Fast intrateam reviews to quickly reach decisions that need some discussion but not a full review

- quick write-up describing the decision to be made, a light-weight design doc

- teammates then whiteboard and discuss their options, provide input, and make a decision

- Don’t surprise people (Your own operations work when constructing a design)

- gently and incrementally ease people into your design proposal

- instead, when you do your initial research, get early feedback from other teams and tech leads

- feedback sessions don’t need to be formal or scheduled.

- make people aware of what you’re doing to give an opportunity for feedback and to get them thinking about your work

- keep people up-to-date

- give updates in status meetings and standups

- pay attention second-order effects in your proposed changes and whom this might impact; notify affected teams of upcoming changes

- be inclusive— pull people into brainstorming sessions and listen to their thoughts

Chapter 11 - Creating Evolvable Architectures

Requirements volatility or changing customer demands is an unavoidable challenge for software projects.

- Product requirements and context will change over time; your application must change as well.

- Can cause instability and derail dev

Managers try to deal with requirements volatility using iterative dev processes like Agile development

As an IC, you can do your part by building evolvable architectures

- eschews (deliberately avoids) complexity, the enemy of evolvability

Listed below are techniques that can make your software simpler and thus easier to evolve

Understanding Complexity

John Osterhout writes “Complexity is anything related to the structure of a system that makes it hard to understand and modify the system”

-

Two characteristics:

- high dependency

- high obscurity Consider a third: high inertia

-

high dependency

- leads to software to rely on other code’s API or behavior

- due to tight coupling

- components are highly dependent on each other

- due to high change amplification

- a single change requires modifications in dependencies as well

- Want to minimize tight coupling and change amplification

-

high obscurity

- makes it difficult for programmers to predict a change’s side effects, how code behaves, and where changes need to be made

- examples:

- God objects that “know” too much

- global state that encourages side effects

- excessive indirection that obscures code

- action at distance that affects behavior in distant parts of the program

- APIs with clear contracts and standard patterns reduce obscurity

-

high inertia

- software’s tendency to stay in use

- ex:

- easily discarded code used for a quick experiment has low inertia

- a service that powers dozen business-critical applications has high inertia

- complexity’s cost accrues over time, so high-inertia, high-change systems should be simplified, while low-inertia or low-change system can be left

How to Design for Evolvability

Framework:

- KISS - keep it simple, stupid

- YAGNI - you ain’t gonna need it

- avoid premature optimization when dev adds a performance optimization to code before it’s proven to be needed

- have flexible abstractions

- ex: choosing implementation of Apache Kafka vs AWS SQS

- should the interface of the distributed queue have an intersection of the features or union of the features?

- No, both is not the right answer

- Choose one, then refactor later if you need to add more. Focus on reducing complexity. Also more flexible later if you need to add more.

- should the interface of the distributed queue have an intersection of the features or union of the features?

- ex: choosing implementation of Apache Kafka vs AWS SQS

- The best way to keep your code flexible is to simply have less of it

- called Muntzing

- Principle of Least Astonishment

- don’t surprise users, build features that behave as users first expect

- implicit knowledge - anything nonobvious that a developer needs to know to use an API and is not part of the API itself

- common implicit knowledge violations:

- hidden ordering requirements

- hidden argument requirements

- common implicit knowledge violations:

- ordering requirements - dictate that actions take place in a specific sequence

- ex. Method ordering

- avoid by having dependent method invoke submethods:

pontoonWorples(){ if(!flubberized){ flubberize() } //... }

- avoid by having dependent method invoke submethods:

- using the builder pattern - create reusable code to construct object

- make

pontoonWorpleswork only onFlubberizedWorplesrather than allWorples

- make

- ex. Method ordering

- Hidden argument requirements occur when a method signature implies a wider range of valid inputs than the method actually accepts

- use specific types that accurately capture your constraints; when using flexible types like JSON

- at least advertise argument requirements in documentation

- use std libraries and development patterns

- use specific types that accurately capture your constraints; when using flexible types like JSON

- Encapsulate Domain Knowledge

- encapsulate domain knowledge by grouping software based on business domain, helps keep code focused and clean

- Encapsulated domains naturally gravitate towards high cohesion and low coupling

- Software from a devs point of view is typically grouped in layers (frontend, middleware, backend)

- works great for single business domain, gets messy with more applications and requirements

- shared horizontal layers make it too easy for devs to mix business logic between domains

- Domain-Driven Design (DDD) - defines an extensive set of concepts and practices to map business concepts to software (Note: read into more later in career)

Evolvable APIs

Key features: Small, clearly defined, compatible and versioned

- Keep APIs small

- YAGNI

- sensible defaults

- Expose Well-Defined Service APIs

- use std tools to define service APIs

- OpenAPI for RESTful services

- non-REST services use Protocol Buffers, Thrift, or a similar interface definition language (IDL)

- Note: think how gprc generates stubs from protobuf files, what documentation do they add to make it implementation of stubs clear? How does it specifically define parameter types and what design choices make it flexible and backward compatible? (numbering system)

- use std tools to define service APIs

- Keep API Changes Compatible

- Two forms of compatibility: forward and backwards

- Forward-compatible changes allow clients to use a new version of an API when invoking an older service version

- Backward-compatible changes are the opposite: new versions of the library or service do not require changes in older client code

- ex: grpc forward and backwards

message HelloRequest { string name = 1; int32 _deprecated_favorite_number = 2; // keeps old functionality intact due to the field tag number, order in binary wire format sint32 favorite_number = 3; } - Version APIs

- helps communicate which versions of an API can interoperate with which versions of a client

- Keep documentation versioned along with your APIs

- API versioning is most valuable when client code is hard to change!

Evolvable Data

APIs are more ephemeral(lasting for a short time) than persisted data; once the client and server APIs are upgraded, the work is done.

Ranges form simple schema changes to massive migrations and rewrites to match new business logic.

Isolating databases and using explicit schemas will make data evolution more manageable

- Isolate Databases

- shared databases are difficult to evolve and will result in a loss of autonomy — a developer’s or team’s ability to make independent changes to the system

- you will not be able to safely modify schemas, or even read and write, without worrying about how everyone is using your database

- Use Schemas

- Schema: Formal definition of the structure, types, and relationships of data elements within a system

- Don’t hide schemaless data inside schematized data, makes the data more obscure

- Though schemaless has it benefits too:

- when you need to move fast and don’t have a strict idea of requirements

- some data is nonuniform, no standards

- think digitalizing written data, not every book has all the same attributes

- flipping data from explicit to implicit schema is helpful for migrations

- Automate Schema Migrations

- use a migration tool to version database changes to allow for rollbacks if necessary

- Don’t couple database and application lifecycles or don’t put migration into deploy CI/CD

- databases are stateful and long-lived, small changes may have large effects and potential data loss

- a bad migration is harder to rollback

- check data warehouse example below…

- Maintain Schema Compatibility

- when data moves across domains, different domains might have different readers and writers which can affect the identity of the data.

- use schema compatibility checks to detect incompatible changes and use data products to decouple internal and external schemas

- Ex: Data warehouses

- Data warehouses are databases used for analytic and reporting purposes

- Orgs setup an extract, transform, load (ETL) data pipeline that extracts data from production databases and transforms and loads it into a data warehouse

- ETL pipelines depend heavily on database schemas

- dropping the column in a prod db can cause entire data pipeline to stop

- even if it doesn’t stop, downstream users might be using the dropped column for various other applications that would be impacted

- Can also protect internal schemas by exporting a data product (eg. API to gold std data) that explicitly decouples internal schemas from downstream users.

- Data products - offers superior, consistent, and reliable data access

- user-interface: map internal schemas to separate user-facing schemas

- features of the data:

- Exposes clean, validated, and modeled data ready for consumption

- Hides messy internals (e.g., raw logs, upstream quirks)

- Comes with data contracts (schemas, types, meanings)

- Can be used repeatedly across stakeholders

- Allows teams to maintain compatibility with data consumers without having to freeze their internal database schemas

- Data products - offers superior, consistent, and reliable data access

- when data moves across domains, different domains might have different readers and writers which can affect the identity of the data.

Chapter 12 - Agile Planning

The Agile Manifesto

- Values:

- individuals and interactions over processes and tools

- working software over comprehensive documentation

- customer collaboration over contract negotiation

- responding to change over following a plan

- Focuses on collaboration with teammates and customers; recognizing, accepting, and incorporating development releases

Agile Planning Frameworks

- Scrum and Kanban are the two most common

- Scrum - encourages short iterations broken into sprints

- sprints typically 2 weeks

- brief daily stand-up to share updates and call out problems

- after each sprint, teams perform a retrospective to review finished work

- Kanban - defines workflow stages through which all work items transition

- ex: backlog → planning → implementation → testing → deployment → rollout

- limits work in progress (WIP) by limiting the number of tasks in each stage, forcing devs to finish existing tasks

- Scrumban - mashup of the two

- Scrum - encourages short iterations broken into sprints

Scrum

- Planning process

- devs and pms create new user stories and tickets from the backlog are triaged

- stories are assigned story points to estimate their complexity and are broken into tasks

- larger stories are designed and researched with spike stories

- during sprint planning, the team chooses which stories to complete during the next sprints, using story points to prevent over committing

- User Stories

- specific kind of ticket that defines a feature request from a user’s perspective

- in the format “As a <user>, I <want to> <so that>”

- don’t write it as tasks that you need to do focus on the value it brings to the user

- Attributes:

- Estimates - guess at the effort a story takes to implement

- Acceptance criteria - define when a story is complete

- try to write explicit tests for each acceptance criteria

- Tasks

- a single story may need to be broken down into smaller tasks to estimate how long it will take, to share the work between multiple devs and to track implementation progress

- Framework: good trick for breaking down work is writing very detailed descriptions

- Story Points

- team’s work capacity is measured in story points

- story points - an agreed-upon sizing unit (measured in hours, days or “complexity”)

- time vs task complexity

- time: story points = units of time

- task complexity = fib sequence approach, 1 = extra small, 2 = small, 3 = medium, 5 = large, etc..

- Backlog Triage / grooming

- Product managers tend to read over the backlog with engineering manager and sometimes with developers.

- New stories are added, outdated stories are closed, incomplete stories are updated and high priority work is moved to the top of the backlog

- Sprint Planning

- after prework, sprints usually 2 weeks

- Sprint planning meetings are collaborative, eng teams work with pms to decide what to work on and what will fit into sprint capacity

- Sprint capacity - determined by looking at how much was completed in previous sprints

- sprints are locked once sprint planning is done, no new work

Stand-ups

- quick 15 minute meeting scheduled every morning for updates

Reviews

- happens between sprints

- two parts: demonstrations and project review

- reviews celebrates team wins, create unity, give feedback opportunities and keep teams honest about progress

Retrospectives

- talk about what worked and what didn’t work since the last retrospective

- three phases: sharing, prioritization, and problem solving

- reviews vs retrospectives

- reviews focused on the work done in the sprint

- retrospectives focus on process and tooling

Roadmaps

- managers uses product roadmaps for long-term planning

- roadmaps are typically broken down into quarters

- Jan - Mar

- Apr - Jun

- Jul - Sept

- Oct-Dec

- Planning usually take place before each quarter begins, all stakeholders all convene to discuss upcoming goals and work.

- roadmaps are meant to evolve; not meant to be static and reliable docs about what the team will build

Chapter 13 - Working With Managers

What Managers Do

- Mangers build teams, coach and grow engineers, and manage interpersonal dynamics

- Engineering managers work on people, product, and process

- plan and coordinate product development

- also might weigh in on technical aspects of product development, code review and architecture

- manage up: managers work with higher-level executives or directors

- connect engineers with the executives making the business decisions at the top

- Upward management is crucial for getting resources (money and engineers) and making sure the team is recognized, appreciated, and heard

- manage sideways: managers work with other managers

- keeps teams aligned on shared goals

- manage down: managers work with their team

- tracking the progress of ongoing projects

- providing visibility into relative priorities

- hiring and firing

- maintaining team morale

Communication, Goals, and Growth Processes

Processes to maintain relationship with manager:

-

one-on-ones

-

progress-plans-problems

-

objectives and key results

-

1:1

- manager should schedule a weekly or biweekly 1:1 meeting with you

- dedicated time for you and your manager to discuss critical topics, address big-picture concerns, and build a productive long-term relationship

- Framework: what to ask on 1:1

- Big picture

- What questions do you have about the company’s direction?

- What questions do you have about organizational changes?

- Feedback

- What could we be doing better?

- What do you think of the team’s planning process?

- What is your biggest technical concern?

- What do you wish you could do that you can’t?

- What is your biggest problem?

- What is the company’s biggest problem?

- What roadblocks are you or others on the team encountering?

- Career

- What career advice does your manager have for you?

- What can you improve on?

- What skills do you wish you had?

- What are your long-term goals, and how do you feel you’re tracking in them?

- Personal

- What’s new in your life?

- What personal issues should your manager be aware of?

- Big picture

-

PPPs

- status update format; used to help your manager find problems, areas where you need context and opportunities to connect you with the right people

- Framework:

2022-07-02 Progress Debugged performance issue with notification service Plans Add metrics and monitoring to spam detection service Problems Having trouble getting team to code review my PRs- Keep a running log of past PPPs

-

OKRs

- way for companies to define goals and measure their success

- Framework:

OBJECTIVE Stabilize order service KEY RESULT 99.99 percent uptime as measure by heath check KEY RESULT 99th-percentile latency (P99) < 20ms KEY RESULT 5XX error rate below 0.01 percent of responses